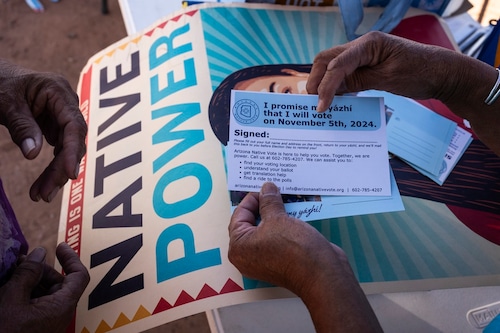

According to a recent study, there are significant differences in Native American turnout, especially for presidential elections, because of structural obstacles to voting on tribal territories.

The Brennan Center for Justice published the report last month, examining 21 states with federally recognized tribal territories where at least 5,000 people live and where over 20% of the population is American Indian or Alaska Native. Researchers discovered that between 2012 and 2022, people who lived off tribal territories in the same states had reduced voter turnout in federal elections by 7 percentage points in midterm elections and 15 percentage points in presidential elections.

According to the Brennan Center, the most recent data revealed that voter turnout was lowest on tribal grounds with a high population of Native Americans, despite previous studies showing that turnout for communities of color is higher in regions where their ethnic group is the majority.

According to Chelsea Jones, a researcher on the study published on November 19, there is a more intense event taking place among Native American communities on tribal grounds.

According to Jones, the study indicates that certain obstacles might be unbreakable in communities with a large Native population since there aren’t enough polling stations or early or mail-in ballots available. Voting by mail is made more challenging by the fact that many people living on tribal territories have unconventional addresses, which do not include house numbers or street names. Because of this, a large number of Native American voters use P.O. boxes; however, the report points out that certain jurisdictions do not mail ballots to P.O. boxes.

Native American voters face additional challenges due to the long commutes to the polling places that are located on tribal territories and the lack of public transit. According to an Associated Press story last month, in remote Alaska Native settlements, polling stations occasionally just don’t open if no one is available to conduct an election, and bad weather can make absentee voting unreliable.

It is a very restrictive situation to be in when you consider that residents of tribal territories must travel 30, 60, or even 100 miles (up to 160 kilometers) in order to vote, Jones added. These are very, very serious obstacles.

Jones said that they discovered that in a number of locations, including states where it is lawful, Native American voters were not permitted to cast ballots using their tribe identification cards. According to Jones, all of these ballot-related obstacles may foster mistrust of the system and result in decreased turnout.

The Brennan Center report also emphasizes a persistent problem with comprehending how or why Native Americans cast their ballots: a dearth of reliable data.

When it comes to researching Native American communities, particularly in relation to politics, there are significant data disparities, Jones stated.

According to Stephanie Fryberg, director of the Research for Indigenous Social Action & Equity Center, which examines systemic injustices experienced by Indigenous people, Native American communities are frequently left out of polling data and, when they are, their inclusion in the studies does not always reflect broader trends for Indigenous voters.

According to Fryberg, a psychology professor at Northwestern University, polling is often not in a strong position to serve Indian Country. Some theories that are promoted as the best practices for polling don’t apply to Indian Country because of the location and the challenges of interacting with members of our community.

Several Indigenous experts, including Fryberg, a member of the Tulalip Tribes in Washington state, criticized a recent Edison Research exit survey that revealed 65% of participating Native American voters supported Donald Trump. None of the jurisdictions in the poll were on tribal territories, and the poll only polled 229 self-identified Native Americans, a sample size she claimed is too tiny for an accurate assessment.

According to Fryberg, you’re already removing a potent viewpoint there.

That polling data has caused a lot of confusion, according to the Indigenous Journalists Association, which called it extremely irresponsible and deceptive.

The survey’s objective is to represent the national electorate and have enough data to also look at significant demographic and geographic subgroups, Edison Research acknowledged in a statement to the Associated Press, despite the polling sample being tiny. The disclaimer states that the poll has a possible sample margin of error of plus or minus 9%.

“This data point from our survey should not be taken as a definitive word on the American Indian vote based on all of these factors,” the statement says.

As citizens of sovereign nations, Native Americans have political identities in addition to belonging to an ethnic group. “Data cannot accurately capture voting trends for those communities if respondents are allowed to self-identify as Native Americans without being asked follow-up questions about tribal membership and specific Indigenous populations,” Fryberg added.

According to both Fryberg and Jones, academics and legislators would need to address the unique needs of Indigenous communities in order to improve statistics about and voting possibilities for Native Americans. Jones stated that fair in-person voting choices would be provided in each precinct on tribal territory if the Native American Voting Rights Act, a bill that has stalled in Congress, were passed.

According to Jones, this is not a problem that exists nationwide. It is unique to tribal territory. Therefore, we require measures that specifically address that.

By Brewer, Graham Lee The Associated Press. Graham Lee Brewer is a member of the AP’s Race & Ethnicity team who lives in Oklahoma City.

Note: Every piece of content is rigorously reviewed by our team of experienced writers and editors to ensure its accuracy. Our writers use credible sources and adhere to strict fact-checking protocols to verify all claims and data before publication. If an error is identified, we promptly correct it and strive for transparency in all updates, feel free to reach out to us via email. We appreciate your trust and support!